He threatened to rape me. Police actually responded. A MAGA incel's day in court.

My day in court yesterday against the man who threatened me online

Editor’s note:

This piece discusses targeted harassment, sexual violence threats, and extremist intimidation. While these details are necessary to document how coordinated harassment operates in practice — and how institutions routinely fail to respond — they may be distressing for some readers. Please take care while reading, and step away if you need to.

If you’ve been a subscriber or follower of mine for a while, you already know that my work no longer exists solely on the page. It has spilled into my real life in ways that are frightening, exhausting, and impossible to ignore.

Over the past several months, I’ve dealt with a sustained wave of violent threats — including rape threats — and even a home invasion, all tied to radicalized MAGA extremists who view truth-telling as an existential threat.

This is not new terrain for me.

Coordinated harassment, smear campaigns, and targeted intimidation have become a routine occupational hazard of my writing and advocacy. Over the years, that reality has put me in contact with researchers and experts who study disinformation and online radicalization for a living — people who understand how these campaigns are manufactured, funded, and deployed.

One of them, the always-prescient Jim Stewartson, warned me, explicitly, that a coordinated operation was forming around me nearly a month before I fully understood what was happening back in 2021.

At the time, I didn’t believe it. I should have listened.

As a climate scientist and data journalist, I’ve been dealing with online harassment for most of my career. Anyone who speaks publicly about climate change, public health, or government accountability eventually becomes a target. That exposure probably did harden me in ways that made the abuse survivable — if not acceptable.

But “used to it” does not mean “okay with it.”

And it does not mean I ever stopped pursuing accountability.

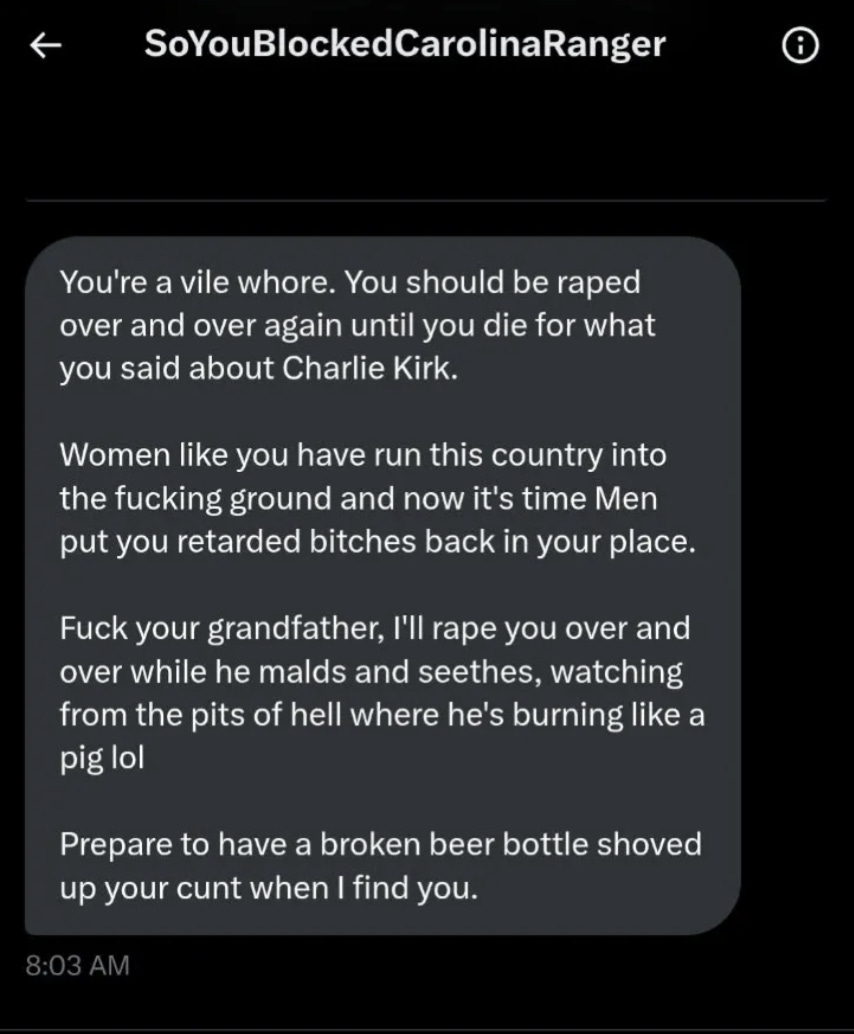

Yesterday, I sat in a courtroom and faced the man who threatened to track me down and rape me with a broken beer bottle.

That moment did not come out of nowhere. It sits at the intersection of years of threats, doxxing, intimidation, and coordinated campaigns designed to silence anyone who refuses to play along. In the chaos that followed the death of a podcaster in Utah last year — a moment that triggered a frenzy of misinformation and rage — I, like many others who spoke plainly and factually about what happened, received more rape threats and death threats than I can count.

This part matters:

I am not exaggerating.

And I am not unique.

I am, unfortunately, experienced.

Since taking on Ron DeSantis nearly six years ago, I’ve dealt with a revolving door of deeply disturbed online abusers. I’ve obtained multiple restraining orders. Several individuals have been criminally charged. And still, a well-funded, coordinated smear operation linked to DeSantis’ political network continues to operate — resurfacing narratives, amplifying lies, and feeding the same ecosystem that produces these threats.

Even when someone left me a voicemail saying, “I’m going to kill you. I’m going to kill your whole family. You’re gonna die, motherfucker,” the FBI ultimately declined to prosecute. After locating the man who made the threat, they determined they could not prove he intended to carry it out.

The threat alone, I was told, was not enough.

That sentence should unsettle you.

Despite repeated disappointment — despite watching violent men skate past accountability again and again — I continued reporting every threat. Not because I believed justice was guaranteed, but because records matter. Paper trails matter. Patterns matter.

After I was placed on the so-called “Charlie’s Murderers” hit list last September, I began documenting and reporting everything.

Many of those investigations traced activity back to European, Israeli, or African bot farms — further confirmation that what looks like organic rage online is often industrialized and paid for. But through those reports, I know of at least four individuals who were identified by law enforcement.

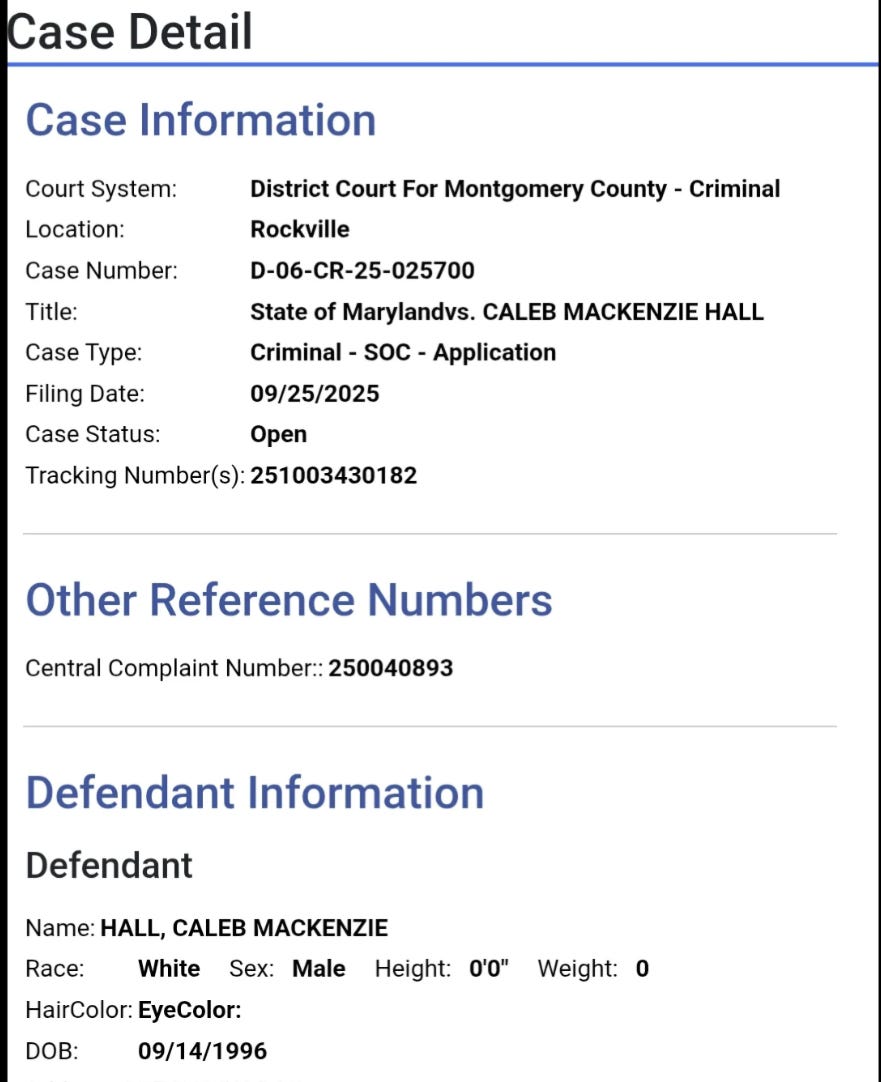

One of those individuals was in court yesterday.

His name is Caleb Hall. He is a 29-year-old white man from Mount Olive, North Carolina. That is the sum total of what I know about him. What I also know is that during the hearing, he stared at me continuously. Unblinking. Fixated.

I’m not going to sanitize this: he set off every alarm bell my body has learned to trust. Potential rapist. Potential killer The kind of presence that makes the air feel unsafe. Anyone who has survived violence understands exactly what I mean.

I have never shied away from naming this behavior for what it is.

Most of the time, I ignore online abuse. I understand that much of it is inauthentic — bought, boosted, and coordinated. I also understand the narrow constraints under which police will act. Unless a threat becomes specific — “I will decapitate you with a forklift” was one memorable example — the system is largely inert.

I’ve been told, more times than I can count, that if I don’t like it, I should just delete my account. As if the price of women’s participation in public discourse is permanent exposure to sexualized violence.

I’ve been told the best police can do is “have a talk” with these men. Or “scare them a little.”

So what follows is not theory. It is not speculation. It is not legal advice written from a textbook.

It is a guide forged through nearly six years of direct experience dealing with violent, radicalized men — and yes, they are always men.

What actually gets taken seriously

1. The threat must be explicit.

Statements like “I hope you die” or “I hope someone does X to you” are violent and disturbing, but they are generally not treated as actionable threats. The distinction law enforcement makes — whether we like it or not — is whether the speaker is threatening to carry out the violence themselves.

I’m often sent screenshots by people asking whether a message is “enough.” My answer is always the same: if you feel unsafe, report it. Always create the paper trail. My guidance here is about managing expectations, not discouraging action.

2. The threats must be violent, specific, and usually repeated or multi-platform.

If someone threatens to spit in your coffee, no agency is going to dedicate resources to tracking them down. The threats that have led to investigations in my cases were graphic, specific, and often repeated — or delivered across multiple platforms.

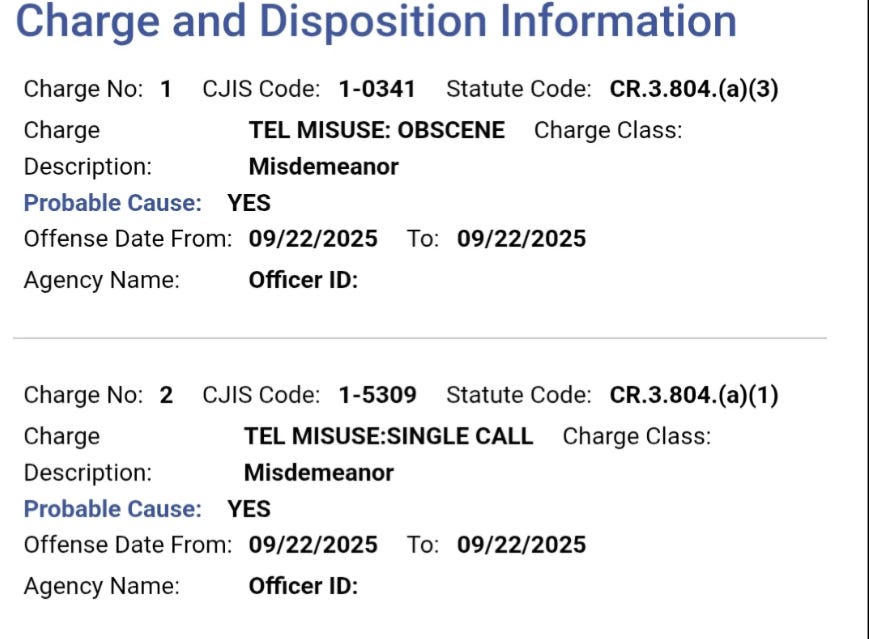

Caleb Hall sent a threatening message on X and followed it with harassing phone calls. Another individual made multiple threatening calls. Another sent a sustained series of messages. The pattern is consistent: the more effort someone puts into threatening you, the more seriously authorities are likely to take it.

That is not how it should be.

But it is how it is.

And until the law catches up with the reality of coordinated online violence, women — especially women who speak inconvenient truths — are left navigating this terrain largely on our own.

I will keep documenting it.

I will keep naming it.

And I will keep showing up, even when the system would rather I disappear.

Though I am extremely grateful both law enforcement and the state took this threat seriously, despite the graphic threat of repeated rape, Caleb Hall was only charged with two misdemeanor counts for what he did (for now, at least).

Why the law keeps failing — and how it must change

What makes this all harder to stomach is that none of it exists in a legal vacuum. The failure here is not just cultural; it is structural.

Most state and federal threat statutes were written for a pre-internet world — one where threats were isolated, local, and singular. They are poorly equipped to deal with modern harassment campaigns that are distributed across platforms, anonymized through intermediaries, and deliberately calibrated to stay just below prosecutorial thresholds.

Intent is the highest bar — and the easiest loophole.

Law enforcement is often forced to prove that a person not only issued a threat, but intended to carry it out. That standard collapses in the face of stochastic terrorism, where violence is encouraged indirectly, repeated endlessly, and outsourced to whoever finally decides to act. By the time “intent” becomes provable, someone is already hurt or dead.

There are clear reforms that would make a difference:

Threat aggregation statutes that allow repeated or multi-platform threats to be treated as a single course of conduct, rather than isolated incidents.

Explicit recognition of online harassment campaigns — including coordinated doxxing, rape threats, and stalking — as criminal harassment, not “speech.”

Lower evidentiary thresholds for protective action, such as restraining orders, when threats involve sexual violence or targeted fixation.

Dedicated cyber-harassment units with the training and resources to investigate threats that cross jurisdictions and platforms.

None of this infringes on free speech. Threats are not speech. Coordinated intimidation is not debate. And waiting for someone to be harmed before taking action is not justice — it is negligence.

My ask of you: Be diligent, vigilant and advocate for change.

If you take one thing from this piece, let it be this: documentation matters, and silence helps no one but abusers.

If you are being threatened:

Report it, even when you are told it “won’t go anywhere.”

Save everything. Screenshots, voicemails, timestamps, URLs.

Create the paper trail anyway — because patterns only exist if they are recorded.

If you witness this happening to others:

Do not minimize it. Call it out.

Do not tell women to “log off.”

Do not treat coordinated harassment as internet drama instead of what it is: a form of political violence.

And if you are a lawmaker, journalist, platform moderator, or researcher reading this: stop pretending these are edge cases. They are not. They are the system functioning exactly as designed — to exhaust, isolate, and silence.

I will keep writing.

I will keep reporting.

And I will keep showing up in courtrooms and public records alike — not because I am unafraid, but because retreat is precisely what this ecosystem is built to force.

Sunlight is still the only disinfectant we have.

Good Lord Rebekah. I am so sorry you are going through all this. I had no idea our laws were so abysmally ineffective on this issue. Thank you for the hard-won information.

Misdemeanor telephone misuse charges? Somehow I think that if I were to leave the exact same messages to a low-level member of the Trump maladministration or the DeSantis regime I'd be facing charges just a tad bit more serious.