Voter registration should be automatic - no ID's required.

A brief-ish history of how advanced registration and ID laws have been used to target women, immigrants, the poor, and minorities.

Dear Readers:

Democracy doesn’t usually collapse in one dramatic moment.

It erodes quietly, through paperwork, deadlines, and “reasonable” barriers that only apply to some people.

The SAVE Act is being marketed as election integrity.

But history shows these systems were built to manage who gets to participate.

I spent days digging into the history, the data, and the propaganda behind modern voter suppression efforts, and laid it all out clearly in my latest piece.

If you value independent, evidence-based reporting that connects today’s policies to their historical roots, please consider supporting my work.

Your paid subscription keeps MesoscaleNews.com alive—and keeps this kind of accountability journalism accessible.

Read the piece.

Share it.

Support the work if you can.

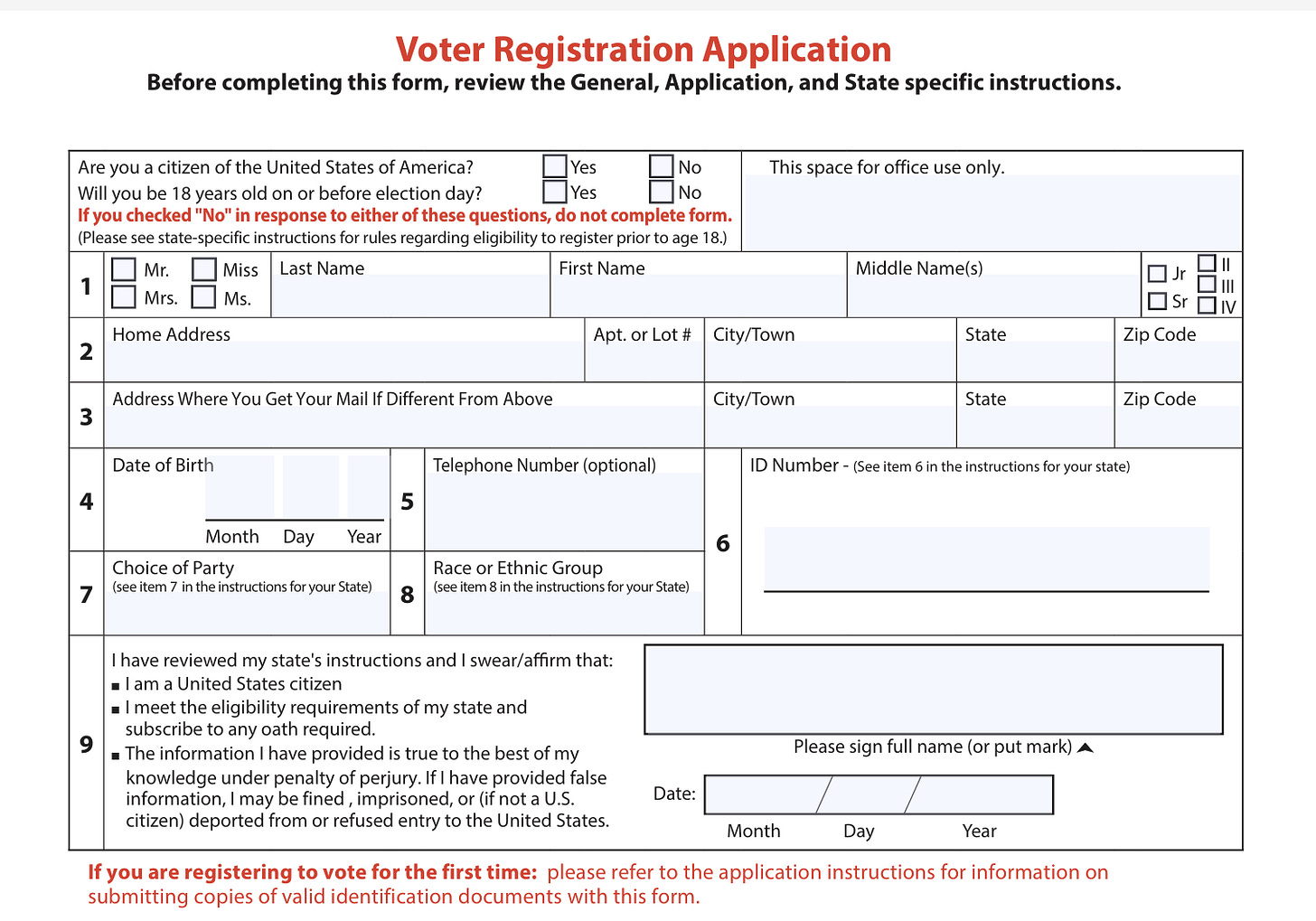

As the law stands now, and has stood in some recognizable form for nearly a century, the information required to register to vote in the United States is remarkably minimal.

Your name. Your address. Your date of birth. A Social Security number or the last four digits of it. That’s it.

You do not need a photo ID. You do not need a birth certificate. You do not need a passport. You do not need to prove citizenship with documents in order to register.

In every state where voter registration is not automatic, you can register to vote by mail without including a single supporting document in every state in the country1.

This arrangement is not a loophole. It is not an oversight. It is a deliberate system built on redundancy, verification, and penalties that occur after registration, not before. And for as long as we have operated this way, we have had virtually no problems.

Before we get into how the SAVE act and ID laws would radically change our elections, we have to address the history of advanced registration.

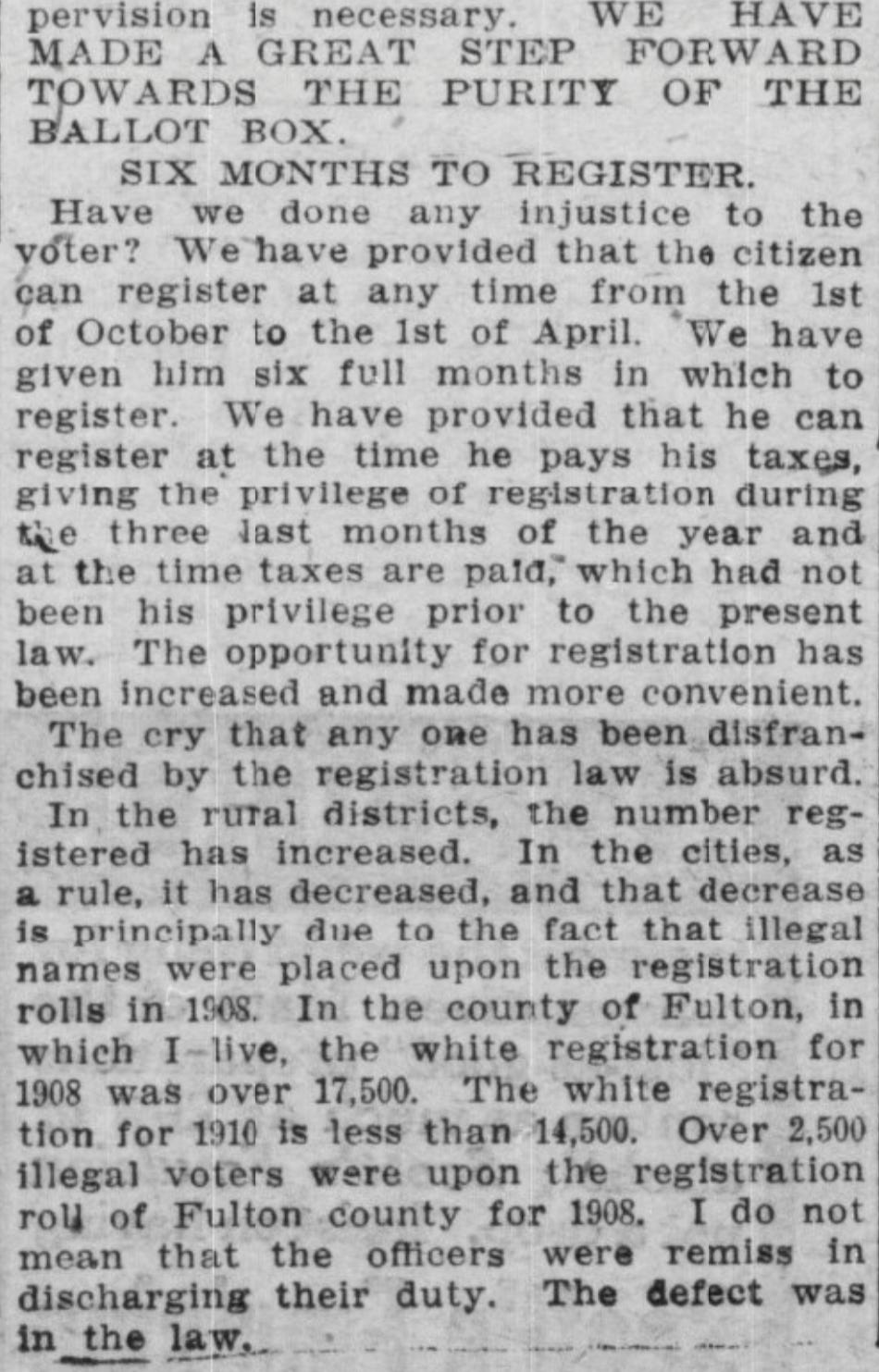

Advance registration was not introduced to protect democracy. It was introduced to control it.

Advance registration spread precisely as property requirements for voting were dropped and immigration from Ireland, Italy, and other parts of Europe increased dramatically.

The timing matters.

The first advance registration law in New York City was explicitly designed to keep Irish immigrants from voting. Across the country, advance registration took hold first in cities, not rural areas, because cities concentrated the poor, immigrants, and racial minorities. Women, notably, were still excluded altogether during much of this period.

When wealthy, white elites realized that they were losing their monopoly on political power, they did rush to argue openly for disenfranchisement. They argued for “order.” For “integrity.” For “administration.” They built systems that looked neutral on paper and functioned as filters in practice.

The mechanics were often absurd.

In New Jersey in the 1860s, you could only register on the Thursday before the election. The controlling parties knew workers would likely not be able to get off both the Thursday before election day and the election day itself.

Some states required voters to list the name of their landlord, employer, and describe where that person lived. Others mandated in-person registration on specific days of the week or specific days of the year, regardless of whether a working person could realistically attend.

New York City once required in-person registration on Saturdays and on Yom Kippur, a choice so nakedly aimed at Jewish voters that it barely bothered to disguise itself. These laws were not about preventing fraud. They were about preventing participation.

And yet, even with all of this history, the modern system remains strikingly permissive by design. Registration requires minimal information because eligibility is verified through cross-checks with existing databases.

False registration is a felony. Voting while ineligible is a felony. Ballots are tracked. Signatures are matched. Lists are audited. The checks happen downstream, where they belong, not at the front door where they can be used to exclude.

This is the system the SAVE Act seeks to upend.

Under the SAVE Act, registering to vote would require documentary proof of citizenship, such as a passport or birth certificate. That sounds simple until you consider who actually has those documents readily available.

Millions of Americans do not.

Passports cost money. Birth certificates cost money. Replacements cost money. Accessing them requires time, transportation, stable housing, and often internet access. It requires navigating bureaucracies that are themselves understaffed, backlogged, and increasingly hostile.

This burden does not fall evenly.

Women are disproportionately affected because name changes after marriage or divorce frequently create documentation mismatches. A birth certificate that does not match a current legal name becomes a barrier, not evidence.

Immigrants who became citizens decades ago may never have had a passport and may face enormous hurdles retrieving original naturalization records.

Poor Americans, especially those born at home, born in rural areas, or born in the Jim Crow South, are far more likely to lack certified documentation entirely.

Advance registration deadlines compound this inequality. When registration is pushed weeks or months before an election and paired with documentary requirements, every delay becomes disqualifying. A missing document is no longer an inconvenience; it is a lost vote. A bureaucratic error becomes permanent exclusion. The SAVE Act would transform registration from a civic gateway into a gauntlet.

All of this is justified with a single, endlessly repeated false claim: voter fraud.

It is a claim that collapses under even minimal scrutiny. Comprehensive reviews by election officials and federal agencies have consistently found voter fraud to be vanishingly rare.

Not common enough to justify mass disenfranchisement. Not common enough to justify rewriting the rules of participation. Not common enough to explain a single election outcome, let alone an entire movement.

And yet the myth persists, because it is useful.

The lie of rampant voter fraud creates moral cover for laws that make voting harder. It reframes exclusion as protection. It allows politicians to claim they are defending democracy while quietly narrowing the electorate. This is not new. It is the same story told with new vocabulary, the same fear dressed up as procedure.

For nearly a century, the United States has operated a registration system that balances access with accountability. It has mostly worked. The problems it supposedly solves do not exist. The harms it would cause are predictable, documented, and historically familiar.

When lawmakers insist that voting must be harder to be legitimate, they are telling you something important. They are not afraid of fraud. They are afraid of voters.

And they always have been.

While the SAVE act seeks to make voting harder, we should be advocating to make it easier.

Automatic registration is what a functioning democracy does when it actually believes voting is a right instead of a scavenger hunt.

The U.S. already runs on paperwork defaults everywhere else that matters: taxes, Social Security, draft registration, jury duty. But when it comes to voting, we insist the burden sits on the individual, and then we act shocked when the people with the least time, least money, least stable housing, least flexible jobs, and least access to documents are the ones most likely to fall through the cracks.

AVR flips that script. It makes registration an opt-out default during routine interactions with government agencies, and it can update addresses automatically when people move, which is where a huge amount of “registration failure” actually lives.

The measurable effects aren’t hypothetical.

Oregon’s first-in-the-nation program added more than 272,000 people to the rolls, including tens of thousands who were unlikely to have registered otherwise, and it produced new voters in the very first presidential election after implementation.

Reports also found that the voters brought in through AVR skewed younger, lower-income, more rural, and more ethnically diverse, meaning the policy didn’t just grow the electorate, it made it look more like the state.

And when you look at turnout directly, the best research tends to find what common sense predicts: removing bureaucratic steps increases participation, especially for people hit hardest by churn and instability.

A causal study exploiting a natural “cutoff” for movers in Orange County, California found automatic voter re-registration increased turnout by about 5.8 percentage points for the affected movers. That’s not a vibe. That’s a measured reduction in the penalty people pay for changing apartments, escaping a bad landlord, leaving an ex, or chasing work.

And here’s the part the “integrity” crowd never says out loud: automatic registration improves list accuracy, too, because it replaces paper forms and manual processing with electronic transfers and routine updates.

That means fewer errors, fewer mismatches, fewer provisional ballots, fewer “you’re not on the rolls” surprises.

It is a pro-voter reform and an administrative modernization at the same time, which is why the evidence on participation gains keeps showing up alongside evidence of better-maintained rolls.

If the goal were truly confidence and clean voter lists, policymakers would be racing toward automatic registration and automatic updates.

Instead, we get bills like SAVE that manufacture new documentation hurdles and call it “security,” while the real-world result is predictable: more eligible people blocked by paperwork, more time off work required, more last-minute chaos, more dropped registrations when people move, and a system that quietly selects for the voters who can afford the friction.

10 US States have automatic voter registration and do not require registration in advance of elections by the voter. Source: https://www.lgbtmap.org/democracy-maps/automatic_voter_registration

I hear you, Rebekah, and voter suppression in our country is indeeed a sad story. I honestly don't see, though, how a person can operate in today's society without having some sort of photo ID. I can't cash a check (remember those) or pick up a prescription without having to present my photo ID, a FL driving license. Lots of stores in FL won't sell you a beer without photo ID. And, of course, you can't get a photo ID without a birth certificate. Vivious circle. What concerns me most about voter supression is suppression of the vote itself by the laws now in effect in many southern states empowering their state legislatures to overturn the vote if they don't like the results their secretaries of state gave to them. I can see that happening in the midterms. Scary.

Like the stupid Real ID requirement. You need every document in one name (or produce your name change paperwork after divorce). Eminently harder on females.