The Map That Doesn’t Match: Vaccine Exemptions and America’s Public Health Divide

Why vaccine exemptions don’t fit America’s usual divides

Everyone knows the map.

For almost every social or economic issue — poverty, anti-LGBTQ+ laws, educational access — America’s geography tells a familiar story.

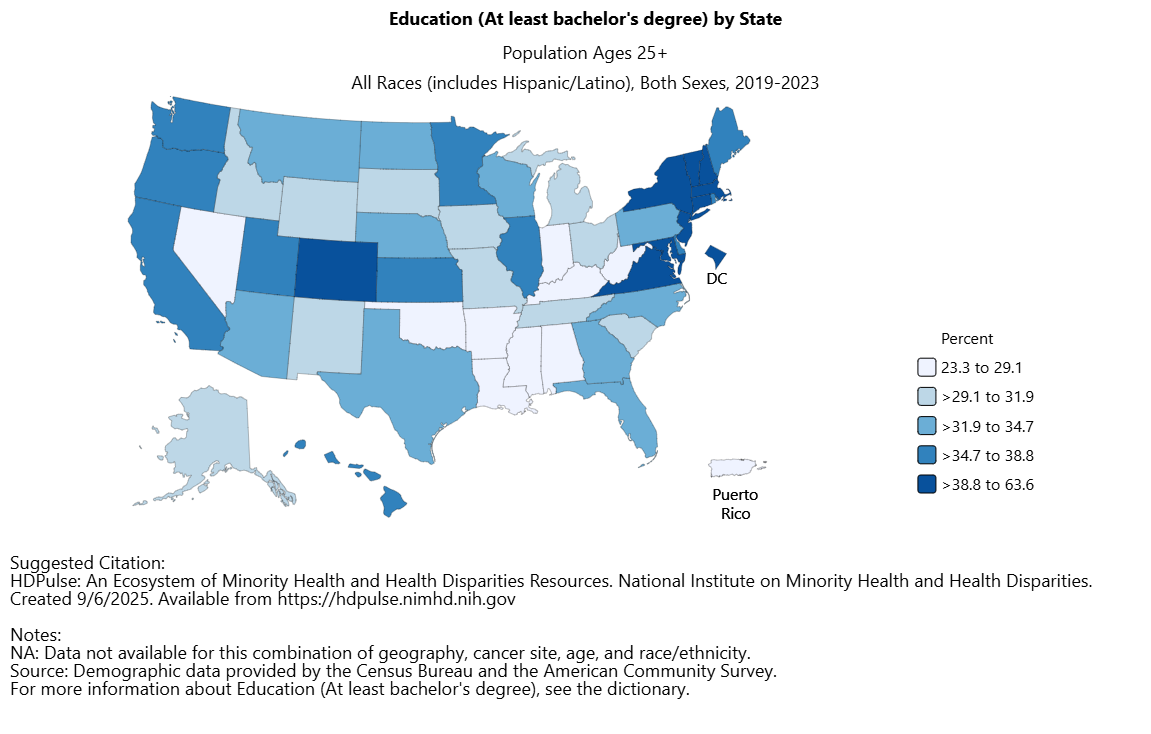

The map of college education shown below mirrors patterns we’ve seen again and again: the Deep South and Mountain West trailing near the bottom, East and West coasts perched near the top.

That fami…