Climate, Justice, and the world Katrina Left Behind

Marking 20 years.

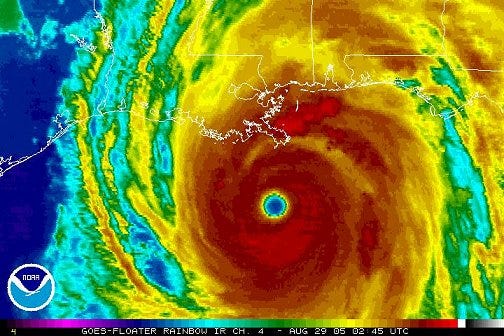

At 11:10 AM CT on August 29, 2005, 120 mph (200 km/hour) winds battered the Mississippi coastline, bringing a record-breaking 28 foot storm surge with it, breaking the earlier record held by Hurricane Camille (1969) by almost four feet.

At 11:10 AM CT on August 29, 2005, I was 16 years old, dancing in the wind and rain of Hurricane Katrina as she made he…